It all began when three hyperactive children in striped pajamas appeared on the television screen. With balaclavas on their heads, these kids started “stealing the colors” from unfortunate victims by taking their photos using Kodak Gold film. That summer of 1995, I did the same (though without pajamas or a strange hat). Armed with a disposable camera, I played paparazzi, capturing images of my family members. Years later, as an adult, I experienced a sudden wave of nostalgia upon stumbling upon these forgotten photographs. I recognized my family, and suddenly, that summer came rushing back to me, thanks to the colors I had “stolen.” This unique ability of photography—to make us relive an immutable past—sparked in me not only a passion for the medium but also a question about its future in light of the rise of generative artificial intelligence.

Authenticating the Past Reality

The photographer is not the only one capable of “stealing” colors. A painter does the same. However, while both media can depict a scene, photography does so with a far greater degree of fidelity. Because of this, it was the first medium perceived as capturing reality without any intermediary. Unlike a painting, a photograph is not the result of an artist’s potentially compromised interpretation but rather the outcome of a chemical process over which the photographer has only limited influence (the choice of time and place of the shot). Thus, whatever is captured must have necessarily existed at the moment the photo was taken. Beyond its representational power, photography also possesses a unique ability to certify past events.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes that the essential characteristic of photography is to state, unequivocally: “that has been.” Since a photograph results from a physical interaction between reflected light and a photosensitive material, it is necessarily an emanation of past reality. The spectator (as Barthes calls the person viewing a photograph) cannot deny that at the moment the shot was taken by the operator (the photographer), the spectrum (the subject) was indeed in front of the camera. This is the distinctive power of photography: beyond representing reality, it authenticates past and immutable reality. This is also the source of photography’s emotional impact—it presents us with the specters (hence the Latin term « spectrum » used to describe the subject) of a bygone past, one we can no longer change.

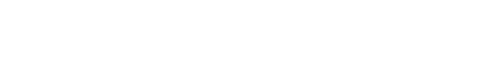

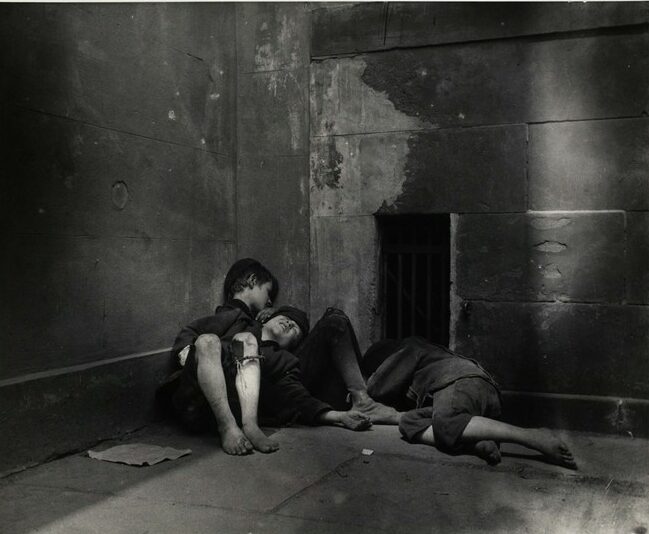

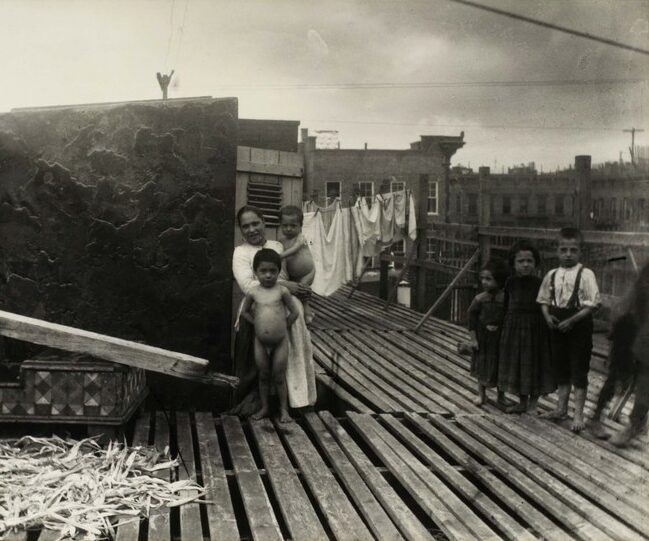

It is therefore no surprise that, soon after its invention, photography became a documentary tool. At the turn of the 20th century, American journalist Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives, documenting, through numerous photographs, the unsanitary living conditions of newly arrived immigrants in New York. By revealing what had previously been hidden from the public eye, Riis managed to generate enough pathos and influence to change building and housing regulations. His written accounts in newspapers had a limited impact, but once his photographs—authenticating the reality of the slums—were published, they triggered real change. Similarly, the photographs of sociologist Lewis Hine played a crucial role in the enactment of child labor laws. His images documenting young workers across the United States brought their harsh working conditions to life for the public.

Thanks to their seemingly tamper-proof physical creation process and their ability to depict reality with an enhanced degree of accuracy, photographs hold significant trust capital with their audience. They enjoy a sort of “presumption of innocence” in the eyes of the public… But how can we ignore the omnipresence of retouched images today? What remains of that trust capital when modifying a scene after capturing it has become so effortless?

Is It Photoshopped?

While photography can indeed certify that a photographed scene actually took place, it says nothing about the specific context of that scene. Today, we know that Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville by Robert Doisneau was not a spontaneous shot but a staged scene featuring two theater students paid for the occasion. Similarly, Jacob Riis, mentioned earlier, had impoverished children in New York pose to better illustrate his point. These examples highlight the fact that photographs are also constructed by the photographer’s hand. The photographer inevitably makes choices in both space and time when capturing an image. These choices may be more or less biased depending on their intentions. So what remains of photography’s ability to authenticate reality when the scene itself is staged? One cannot blame photography for failing to capture what is deliberately left out of the frame. Photographs have only ever attested to the fact that, at a given moment, subjects were indeed present when the scene was captured. But it is important to remember that they reveal nothing about the photographer’s intentions or the reasons behind the scene itself.

Photography, therefore, turns out to be less uninfluenced than it initially seems. While its intrinsic ability to declare “that has been” is not fundamentally challenged by staged scenes, these manipulations represent an initial breach—one that begins to erode the “presumption of innocence” (that is, the presumption of truth) that gives photography its power.

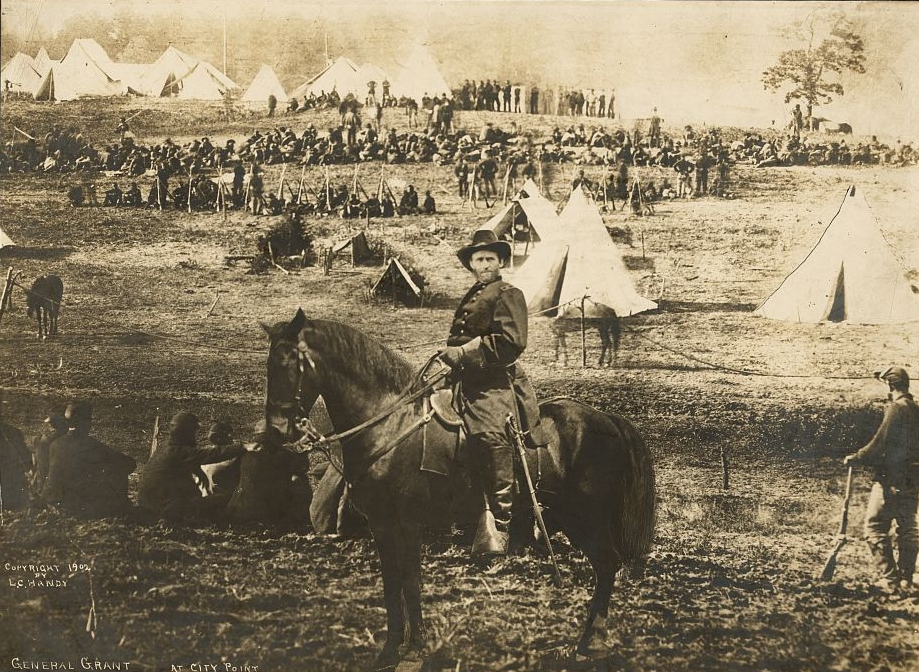

Various retouching techniques, introduced early on and applied after the shot was taken, only worsened this erosion. Editing a landscape or artistic photograph to enhance its aesthetic quality (such as Ansel Adams’ famous dodge and burn technique) may be understandable, but outright manipulations pose a more significant issue. Around 1860, portraitist Thomas Hicks altered a photograph of politician John C. Calhoun by replacing his head with that of Abraham Lincoln. Four years later, a composition of three separate photographs was used to depict General Ulysses S. Grant on the front lines of the Civil War. The reason for such alterations is clear: because photography holds a high level of trust with its audience, it becomes an even more attractive tool for political propaganda. Mao Zedong, Stalin, and Mussolini were all known for manipulating photographic representations of themselves.

If such manipulations remained rare due to the technical skills required, the invention of film and, later, the digital revolution significantly facilitated retouching and image composition. The frequency of these techniques grew exponentially in the late 1980s with the invention of Photoshop. The widespread adoption of retouched images came at a steep cost: a substantial loss of public trust, giving way to generalized skepticism. Today, it is exceedingly rare to see unedited photographs in advertising, though certain bastions, such as photojournalism, continue to resist. In 1982, National Geographic had to issue an apology for altering the aspect ratio of a photograph of the Giza pyramids on its cover. More gravely, in 2003, photographer Brian Walski manipulated an image taken during the Iraq War to make it appear more dramatic by compositing multiple shots taken minutes apart. The final result depicted a soldier pointing his weapon at a man holding a child in his arms.

Overwhelmed by the omnipresence of retouched images, the public has grown more educated, realizing that a photograph does not necessarily correspond to what was originally captured. Little by little, photography has lost its once-unique ability to authenticate the past, becoming instead a source of suspicion. History itself is sometimes questioned: Did humanity really walk on the Moon?

A reversal has taken place. Photography has shifted from a “presumption of innocence” to a state of presumed guilt. Photographs alone are no longer sufficient to tell the truth of what has been.

DALL-E, Draw Me a Sheep

The recent advances in so-called generative artificial intelligence allow us to glimpse a world where photographs are no longer necessarily captured by photographers equipped with cameras but are instead created by narrators giving instructions to a computer program. DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion are just a few examples of tools already capable of generating photorealistic images from text prompts. These AI systems create synthetic photographs—in more ways than one—by analyzing millions of images that are themselves of varying degrees of authenticity.

How can one not think of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave? Deprived of access to reality itself, generative AIs consume millions of projected shadows—selected by their creators—before synthesizing them into new images. The content they generate corresponds to no actual reality. In this way, they resemble illustration—like painting or drawing—far more than pure photography. Furthermore, the instantaneous nature of these tools may give the illusion that they are entirely free of human influence. When it takes only seconds to create an image from a text prompt, it is easy to believe that these tools leave no room for manipulation. Yet, the reality is quite the opposite: synthetic images are merely recompositions of representations that have been deliberately chosen by a distant and often unknown intermediary.

For instance, when a journalist from Bloomberg entered the prompt “CEO” into Stable Diffusion, the majority of generated faces had white skin, whereas the results were much more diverse when the journalist used prompts referring to lower-income jobs. Compared to real-world demographic data, the biases in AI-generated images turned out to be worse than the actual societal reality.

Réalisées automatiquement, à moindre coût et sans appareil, nul doute que ces “photographies” deviendront pourtant aussi omniprésentes que la retouche de clichés aujourd’hui. Nina Schick, auteure et experte sur le sujet des intelligences artificielles génératives, prévoit déjà que 90% du contenu en ligne sera créé de cette manière d’ici 20251. L’abondance de contenu synthétique mais indiscernable de clichés authentiques fera sans doute perdre au public le peu de capital confiance qu’il accordait encore à la photographie, au risque de la reléguer définitivement au rang de simple illustration. Les intelligences artificielles finiront ainsi probablement le travail d’érosion de la crédibilité de la photographie que la retouche avait commencée à la fin du XIXème siècle.

Saving Photography Through Third-Party Authentication?

Does this mean the end of photography? Probably not. The desire to capture a moment will always remain, and our smartphones serve as ever-ready devices, primed to snap a scene in an instant. However, these authentic photographs (provided they are not significantly altered by filters) will likely never regain the same level of credibility as the early 20th-century images captured by Jacob Riis or Lewis Hine.

Yet, photography—as an authentic record of the past—deserves to be preserved and distinguished from heavily edited images or those generated by artificial intelligence. We must be able to differentiate between the photos taken on the Moon in 1969 and synthetic images designed to cast doubt on the truth of the lunar landing.

Some Initiatives Are Already Moving in This Direction. In response to staged photographs and the temptation of digital retouching, the National Press Photographers Association has established a code of ethics stating that digital alterations must not compromise the integrity of an image’s content or context. Any manipulation that adds, removes, or modifies elements in a way that could mislead the audience is prohibited. Similarly, in France, since October 2017, it has been mandatory to include the label “retouched photograph” on commercially used images. While this law was initially aimed at protecting public health, it also suggests a possible approach for clearly labeling deepfake-style photographs.

However, experience has already shown that even when synthetic images are labeled with a disclaimer, audiences can still be deceived. As images are shared and reshared, the “generated by artificial intelligence” label often disappears, allowing the picture to be mistaken for reality. For instance, British journalist Eliot Higgins created a series of AI-generated images depicting Donald Trump attempting to flee from police officers on the steps of a New York courthouse. Despite Higgins’ clear disclosure of his intent, as the images spread, their context was lost, and a portion of the audience came to believe them to be authentic.

How Can We Ensure That Authentic Online Content Remains Verifiable? This is a difficult challenge, but the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) has proposed an intriguing concept: sealing provenance and editing information directly into an image file. From the moment a photograph is taken, metadata—such as location, date, and author—would be embedded within the image. Any attempt to alter these details would invalidate its certification of authenticity. At the same time, editing would still be possible with compatible retouching software, but all modifications would be logged in a digital manifest. In this system, audiences would have access to a complete history of an image from its creation to its final version.

A Technical Salvation?

A technical solution to a problem exacerbated by technology? Quite possibly. If widely adopted, this certification system could function similarly to the nutritional labels on supermarket products. However, just as with food labeling, we cannot force the public to actually read the manifest. Likewise, it would not prevent staged photographs from being used to manipulate audiences.

Still, this certification process would enhance transparency by making image traceability accessible. Knowing the location, time, date, and author of a photograph—as well as its entire editing history—would allow audiences to view and share images with full awareness. As Spinoza might say, we are never as free as when we understand the causes of what affects us.

Acknowledgments: Loève Saint-Ourens, Christophe Marques